Fig.1: Charles Austen’s Naval General Service Medal[1]

In 1849 Charles Austen received a distinguished award, the Naval General Service Medal. It was created by Queen Victoria in recognition of participation in significant naval actions between 1793 and 1840, such as an important single-ship capture of an enemy vessel, a larger naval engagement, like the Battle of St Domingo (1806), or a major fleet action, such as the defeat of the Franco-Spanish fleet at Trafalgar (1805).[2] The medal shows a left facing effigy of the Queen on one side and the figure of Britannia on the other. It hangs by a white ribbon edged with dark blue. Clasps, each designating the action for which the participant is honoured, are affixed to the ribbon.

Charles’s ribbon carries two clasps: “Unicorn 8 June 1796,” a reference to a single ship action by the 38 gun frigate, HMS Unicorn,[3] and “Syria” which refers to an extensive campaign in Syria in 1840.[4] These actions are like bookends to a 42 year period during Charles Austen’s long naval career. He was a 16 year old midshipman when the Unicorn triumphed over the much larger French frigate, La Tribune (44 guns). By 1839, during the action in Syria, he was the 60-year-old captain of HMS Bellerophon (80 guns). In this blog, I will explore the two naval actions which Charles’s medal recognizes and consider the significance of this award for Charles.

HMS Unicorn vs La Tribune: A dramatic chase and capture

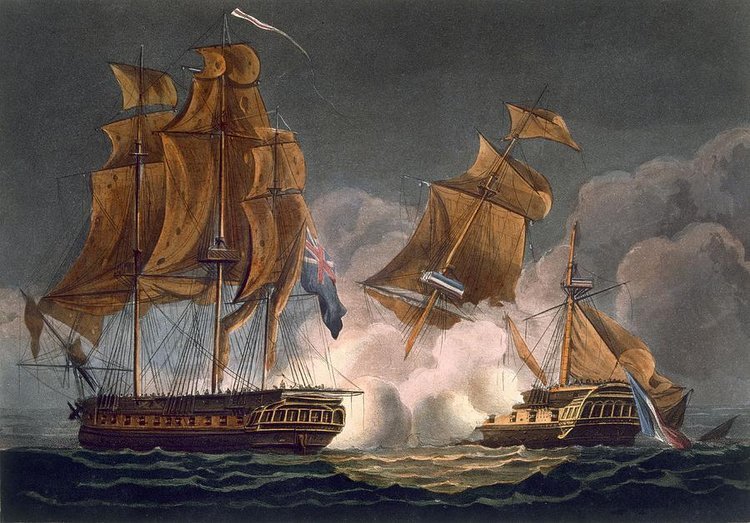

Those aboard HMS Unicorn on 8 June 1796 would long remember that day. As dawn broke, the Unicorn, while cruising west of the Scilly Islands, sighted and gave chase to an enemy frigate, La Tribune.[5] During the day, the French ship ran before the wind, and although the Unicorn gained on her target, she was also subjected to well directed fire, resulting in damage to her mast and rigging. Undeterred, the Unicorn kept up the chase and a running fight for 10 hours. According to her captain, Thomas Williams, “at half past ten at night, having [run 210] miles, we [came] up alongside our antagonist and gave him [broad] sides for 35 minutes.”

As the smoke cleared, the Unicorn realized that she was still in considerable danger. La Tribune was, in Williams's words, “attempting by a master manoeuvre to cross our stern and gain the wind.”[6] Williams and his men responded by “instantly throwing Unicorn’s sails aback, by which means the ship gathered stern way, passed the enemy’s bow, regained her former position”[7] and renewed the attack. The triumphant Williams continued: “the effect of our fire soon put an end to all manoeuvre for the enemy’s ship was completely dismantled,[8] her fire ceased, and all further resistance appearing ineffectual, they called out they had surrendered.”[9] It was a spectacular triumph of seamanship and bombardment for all those aboard the Unicorn.

Fig. 2: Capture of La Tribune by HMS Unicorn on June 8th 1796.[10]

Only similarly significant single ship actions during the French Revolutionary Wars (1793-1802) were deemed worthy of the Naval General Service Medal.[11] The Admiralty recommended only those actions which counted as exceptional accomplishments in which the captain and the men had displayed marked courage and excellent seamanship, and the action was completed with as little loss of British lives as possible. The capture was also deemed praiseworthy if the enemy vessel, although damaged, could readily be repaired and refitted. In such instances, the ship could be recommissioned into the British Navy, thereby adding to the British fighting forces while at the same time reducing the enemy’s fleet.

Evidently, the taking of La Tribune by the Unicorn satisfied these expectations. With a crew of 251 compared to the enemy’s 337, Williams and his men undertook a daring and challenging action, which required bravery, stamina and perseverance. They managed to sustain a running fire for 10 hours over a distance of 210 miles. Moreover, Captain Williams’s leadership was exemplary. Throughout the action he displayed “judicious and seamanlike conduct.”[12] The enemy’s final desperate strategy to cross the Unicorn’s stern and gain the wind was “skillfully defeated”[13] by Williams’s quick thinking and his men’s rapid response. An extraordinary feature of the action was that La Tribune failed to inflict any casualties aboard the Unicorn, whereas 37 men on the Tribune were killed, and 15 were wounded, including her captain, Commodore Moulson. In addition, La Tribune was a valuable prize - only three years old, well built and well designed. She was repaired and commissioned into the British navy as HMS Tribune.[14]

To be a participant in an action of this importance surely thrilled the young Charles Austen. It was his first experience of a long and complex pursuit and capture. We don’t know what specific part he played. As a senior midshipman, he might have been involved in commanding a group of guns in action during the prolonged chase. Charles must have felt some reflected glory, given the public praise for the Unicorn’s remarkable feat. Certainly, the Austen family rejoiced when, soon after the Unicorn’s return to port, King George III knighted Captain Thomas Williams as a reward for his gallant bravery. The Austens had a personal reason for being delighted since Captain Williams had married Mrs Austen’s niece, Jane Cooper, two years earlier. For Charles, the Unicorn action demonstrated what fame and fortune a naval career might bring. If he developed expert naval skills and was lucky enough to have auspicious future commissions and assignments, he too might enjoy a life of adventure, honour and riches. That Charles did come by adventure and honour, at last, is signalled by his award of the second clasp designated “Syria.”

HMS Bellerophon (80) and the Syrian campaign 1840

“Syria” refers to the capture of the Egyptian held fort, St Jean d’Acre, on 4 November 1840 by Austrian, British and Turkish forces and the operations connected with it along the coast of Syria. What was Charles’s involvement in this offensive?

In April 1838, Charles was commissioned as captain of HMS Bellerophon, an impressive ship of the line with a crew of 650, and mounting on her lower, upper and quarter decks seventy-two 32 pounder guns and six 68 pounder guns. Among her crew were Charles’s only sons, nineteen-year-old Charles John, as master’s mate, and fourteen-year-old Henry. When the Admiralty dispatched reinforcements to the western Mediterranean that year, the Bellerophon was among the ships deployed on this mission.[15]

The political mood in the western Mediterranean at that time was tense as Mehemet Ali, the Viceroy of Egypt, had forcibly expanded his control into Syria. Britain and other allied powers demanded he withdraw. Hostilities began when the combined fleets of Britain, Austria and Turkey assembled close to Beruit in August 1840. The Bellerophon, together with HMS Hastings (74 guns) and HMS Edinburgh (74 guns) bombarded the town, which surrendered on 3 October. Tripoli was evacuated by October 22nd, leaving Ali with one last stronghold, the reputedly impregnable fortress of St Jean d’Acre with its surrounding town.[16]

Fig. 3: Bombardment of St Jean d’Acre, 3 November 1840[17]

At 2:00 pm on 3 November, the British and her allies mounted an intensive attack on the town of St Jean d’Acre,[18] its citadel and adjacent fortifications. The first division of British ships, initially led in by HMS Powerful and followed in order by the Princess, Charlotte, Thunderer, Bellerophon, and Revenge, was supported by a second division led by the Turkish admiral[19] with seven additional British warships, three Austrian and two Turkish vessels. The firing, once begun, “waxed furious.” The smoke obscured visibility even before the ships anchored. “The defenders, … [who] wrongly supposed the enemy would not venture close to the fortifications, were deceived as to the exact stations of the [attacking] ships, and thereby gave their guns too great an elevation.”[20] As Clive Caplin has described the scene, “the roar of the cannon was tremendous and incessant. A hail of enemy missiles whistled in all directions over the fleet, while a tempest of shot and shell poured down on the batteries and citadel of the town.”[21]

At 4:30 pm, the defenders suffered a catastrophe. A large powder magazine in the town blew up with a frightful explosion causing dense clouds of smoke. Upwards of 1200 people were killed. Quantities of debris fell on the Bellerophon, which continued to fire at any indications of resistance. During three and a half hours of constant action under Charles’s effective leadership, the Bellerophon expended 160 barrels of gunpowder and 28 tons of cannonballs.

Fig. 4: HMS Bellerophon leading the bombardment of the Syrian fortress at Acre[22]

By 6:00 pm all firing ceased. In addition to the devastation of property and lives caused by the explosion in the town, 300 were killed in the batteries and almost all the guns at the sea face were disabled. The Austrian Archduke Friedrich, who commanded the troops, led a landing party of allied soldiers to capture the citadel. This force, united with 5000 men who arrived from Beruit, took possession of the town of St Jean d’Acre. The combined navies’ action in this last Allied victory in the Egyptian-Ottoman war was complete. The only task left was the transfer of 2000 prisoners to Beruit, a task which Charles Austen shared with three other vessels.

What might this campaign have meant to Charles? Personally, he had the satisfaction of being part of a combined international force which successfully completed a large and significant naval action. He could be proud of his men who had deployed Bellerophon’s gun power with steady and effective industry. To his great relief, Charles's two sons survived unscathed, in fact he lost no men in the intense bombardment.

Subsequently, in addition to being awarded the “Syria” clasp for his participation in the campaign, Charles was picked out for further honour for his particular performance in the action. On 18 December 1840 he was one among only thirteen British captains and one Lieutenant who were made Companions of the Order of the Bath (Military Division), a prestigious British order of Chivalry founded by King George 1 in 1725. Moreover, the Syrian action, which illustrated his competence in battle, enhanced Charles’s naval record and likely contributed to his selection for what would be his last commission, his appointment in1851 as Commander-in-Chief of the East Indies and China Station.

Fig.5: Badge of the Companion of the Military Division of the Order of the Bath

[1] Owned by Charles’s direct descendent David Willan, the medal in currently on display at the Historic Dockyard, Chatham in the exhibit, “Command of the Oceans.”

[2] Other fleet actions include: Camperdown (1797), the Nile (1798), Copenhagen (1801), Abukir (1801).

[3] Only four individuals from the Unicorn action were still alive at the time this clasp was awarded.

[4] 6,978 individuals received this clasp.

[5] Unicorn’s action began as a pursuit, in company with HMS Santa Margaritta, of two French frigates the Tribune, and the Tamise. The Santa Margaritta quickly took the Tamise. The Unicorn continued to chase the Tribune.

[6] Thomas Williams to Admiral Kingsmill, 8 June 1796. The text of Williams’s letter is from a cutting of a newspaper report affixed to the back of a print, titled “The capture of La Tribune by HMS Unicorn …,” after Francis Chesham, in the possession of the National Trust, Gunby Estate, Lincolnshire.

[7] See “Sir Thomas Williams, Royal Naval Biography, ed. John Marshall, 1827.

[8] Only her mizen mast was left standing

[9] Thomas Williams to Admiral Kingsmill, 8 June 1796.

[10] After a painting by Thomas Whitcombe, published in The Naval Achievements of Great Britain from the year 1793 to 1817, London, 1817.

[11] Only 32 single ship actions were recognized.

[12] “Sir Thomas Williams, Royal Naval Biography, ed. John Marshall, 1827.

[13]“ Sir Thomas Williams,” J.K Laughton, revised Andrew Lambert, Oxford Dictionary of Biography.

[14] La Tribune was originally the French frigate, Galathee, launched in 1793. As HMS Tribune, her career in the British navy was short lived. See my blog “Jane Austen’s Naval Brother, Charles, and La Tribune: Milestones in a Naval Career, 1 August 2022.

[15] My account draws on Clive Caplan’s article, “The Ships of Charles Austen,” JAS Report for 2009, 154-5.

[16] See W.L Clowes on the 1840 Syrian campaign, paragraph 17, URL https://pdavis.nl/Syria.htm. The fort had been considerably strengthened since its occupation by the Egyptians in 1837. The defences were very strong towards the sea, where the works mounted 130 guns and about 30 mortars.

[17] By Lt Col William Freke Williams, published in England’s Battles by Sea and Land, 1857.

[18] According to Clowes, “the town was low standing on an angle presenting two faces to the sea, both walled and covered with cannon - in one place a double tier.” See paragraph18.

[19] He was Captain Baldwin Wake Walker RN.

[20] See Clowes, paragraph 11.

[21] See Caplan, 155.

[22] Signed and dated by John T. Baines, Dec. 19, 1840.