Naval officers’ wives during the Napoleonic Wars have long fascinated me—both the real-life ones and those found in fiction, such as in Jane Austen’s Persuasion. While researching the life of Fanny Palmer Austen, I came upon the story of Louisa Berkeley, who married a naval officer in Halifax, Nova Scotia, the same year Fanny Palmer married Charles, Jane’s younger naval brother, in Bermuda. Comparing Louisa’s actions as a naval wife with Fanny’s gave me insights into the significance of Fanny’s relationship with Charles within the naval world they shared. In the process, I discovered how aspects of Fanny’s married life found echos in Austen’s imagining of Sophy, wife of Admiral Croft, in Persuasion. Here are profiles of the diverging and diverting sea going lives of Louisa and Fanny that afforded me a greater understanding of the character of Sophy Croft in Persuasion.

Louisa Berkeley was the eldest daughter of Admiral Sir George Cranfield Berkeley, Charles Austen’s commander-in-chief on the North American Station of the navy, 1806-08. Fanny may even have met the vivacious Louisa, and her sisters, for Sir George brought his family out with him to the North American Station. After a whirlwind courtship in Halifax, Louisa married Sir Thomas Masterman Hardy in St. Paul’s Church on 16 November 1807. Hardy had been Admiral Nelson’s close friend, and captain of his flag ship, HMS Victory, at the Battle of Trafalgar, and had recently been made a baronet, accomplishments which presumably contributed to his attractiveness as a suitor. One wonders if Louisa had any clear idea of what life as a naval wife might entail. She was soon to find out.

After the wedding, Sir Thomas was immediately sent to the Chesapeake Bay area, off the coast of Virginia, where the British navy was determined to contain French war ships already shut up in the Bay. According to a disgruntled Louisa, writing from aboard Hardy’s warship, the 74 gun Triumph, “we spent from December 1807 to April 1808 in the gloomy, desolate [Chesapeake] Bay not allowed to land as the Americans were in such an exasperated state that they might have been disagreeable” (quoted in Nelson’s Hardy and his Wife 1769-1877, by John Gore [1935]). During the whole winter the ship was kept perpetually ready for action and no fires were allowed. In these frigid and far from romantic circumstances, Louisa became pregnant with her first of three daughters. She had no regrets when “at last we were released and I returned to Bermuda where my family were, and soon after . . . [on the Triumph], we returned to England.”

It must have become very soon apparent to Louisa that sharing a naval life with Hardy would have limited attractions for her. They were mismatched in matters of personality and interests. He was a serious, unromantic and uncharismatic 38-year-old, wedded to his career in the navy, whereas she was nineteen, socially ambitious, and fun loving. She scarcely knew Hardy when she married him and their first months together on the Triumph, as she describes them, must have reduced any feelings of “fine naval fervour” that she might have originally felt. She found that she hated to be at sea and very early decided she was uninterested in her husband’s career. In subsequent years she often lived abroad with their three daughters, cultivated the friendship of foreign aristocrats and pursued a life of amusement and entertainment, unconcerned that Hardy was regularly posted on assignments at sea taking him far from England. Louisa was essentially a naval wife in name only.

Fanny held very different views and attitudes about her role as a naval wife. She had the advantage of getting well acquainted with Charles during the two years before they married. She knew him to be kind, caring, charming, entertaining, and very handsome. Beginning with their earliest days together, Fanny saw herself as Charles’s helpmate and supporter. As she lived in Bermuda, the southern base of the North American Station, she understood what the career of a serving naval officer entailed, and she willingly became a participant in naval life. She travelled with Charles on board his vessel the eighteen gun Indian between Bermuda and Halifax on a number of occasions. She experienced at least one horrific storm at sea, but this did not discourage her from sailing with him, including undertaking a North Atlantic crossing to England in 1811. She was attuned to the social role which she was expected to fulfill as flag captain’s wife in Halifax in the summer of 1810 and again during 1812-14 in England, when Charles was flag captain on the 74 gun HMS Namur, which was stationed at the Nore. During this later period, Fanny courageously accepted the challenge of making a home for their family of three daughters on board the Namur.

Some of Fanny’s naval experiences would have been known within the Austen family, and especially by Jane and Cassandra. Fanny had originally been introduced through correspondence within the Austen family and once she was in England, she and Charles paid regular visits to Chawton Cottage, where Jane and Cassandra periodically cared for their children. On one occasion when Fanny and Jane were both guests at Godmersham Park, the estate of Charles’s brother, Edward, Jane wrote to Cassandra, speaking of Fanny in familiar terms. She refers to her as “Mrs Fanny, “Fanny Senior,” “[Cassy’s] Mama”, and part of “the Charleses” (15 and 26 October 1813). She notes that Fanny appears “just like [her] own nice self,” words which suggest Jane had a warm and affectionate attitude towards Fanny. Contacts such as these allowed Jane Austen to learn about Fanny’s unique and diverse involvement as an officer’s wife in a naval world. Crucially, Fanny was able to articulate the complexities of naval life from a female point of view.

Jane’s evident sensitivities to Fanny’s life as a naval wife likely influenced her creation of Sophy Croft in Persuasion. Certainly, there are some key differences between Fanny and Sophy in terms of age and appearance, perceptions of what counts as “comfortable” living on a war ship, and the absence of children to care for and nurture. However, there are striking similarities between the two women in terms of behaviour, attitudes and practical common sense.

Both woman made voyages with their husbands. Fanny sailed with Charles between the bases on the North American station and she travelled to England with him on his frigate Cleopatra in 1811. Sophy crossed the Atlantic four times and accompanied Admiral Croft on many other voyages as well. Additionally, Sophy was familiar with Bermuda, a clue that she has been with Admiral Croft on the North American Station, just as Fanny had been with Charles. Fanny periodically lived on four of Charles’s vessels; Sophy made her home on five of her husband’s ships. Both women staved off periods of sea sickness when under sail.

Both Fanny Austen and Sophy Croft were most content when sharing their husband’s lives. Fanny’s letters speak of her very great pleasure in being in Charles’s company. She frankly admits that she is “never happy but when she is with her husband” (4 October 1813). According to Sophy, “the happiest part of my life has been spent on board a ship. While we were together . . . there was nothing to be feared. Thank God!” Likewise, Jane Austen depicts the Crofts as a “particularly attached and happy” couple. Jane Austen’s appreciation of Fanny’s strong desire to support Charles, to find a community of friends, and to be his constant and affectionate companion, may have influenced her ascription of those traits to Sophy Croft.

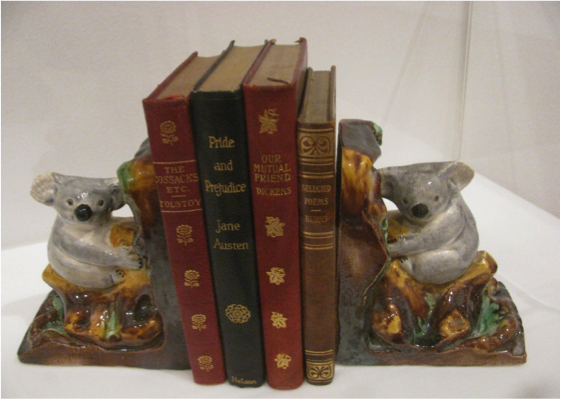

In his biography of Jane Austen, Park Honan suggests that she drew on some aspects of Fanny for Mrs Croft and that she admired Fanny’s “unfussiness and gallant good sense” (Jane Austen: Her Life [1997]). My research into Fanny’s articulate and candid letters written from the Namur, together with records and accounts in her pocket diary, supports this observation. They show her organizing domestic arrangements, acquiring food and necessities for her family at bargain prices and identifying books for the education of her five-year-old daughter, Cassy. In a similar vein, within her domestic sphere, Mrs. Croft proves to be practical and business-like in the matter of arranging for the tenancy of Kellynch Hall and effecting practical alterations once they are resident there.

The three naval wives in question, Louisa, Fanny, and Sophy, make up a diverse trio. Louisa proved to be largely absent from Thomas Hardy’s naval life, but Fanny supported Charles in his naval career with courage, spirit, and dedication. It is fortunate that Jane had a “sister” of Fanny’s ilk, whose richness of experience as a naval wife could contribute to Austen’s creativity when she came to draw the very likable and competent Sophy Croft in Persuasion.

Quotations are from the Penguin Classics edition of Persuasion, edited by D.W. Harding (1965), and the Oxford edition of Jane Austen’s Letters, edited by Deirdre Le Faye (4th edition, 2011).

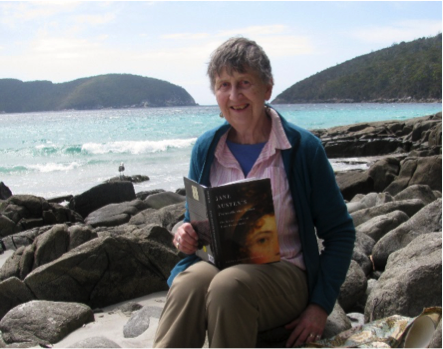

It is likely that Jane’s sensitivities to Fanny’s naval experiences also influenced some aspects of Anne Elliot and Mrs. Harville. For a full discussion of the other naval wives and more about the resonances between Fanny and Sophy Croft, see Chapter 9 in Jane Austen’s Transatlantic Sister: The Life and Letters of Fanny Palmer Austen, by Sheila Johnson Kindred (2017).

First posted on http://sarahemsley.com

![Fig 1: The Terrace Southend, 1808. Note the bathing machines waiting for clients on the shore.[4]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5c1547768ab722e48ecf1942/1629639368925-URADIU6JO9HEDA5V10GH/Terrace.jpg)

![Fig. 2: Sketch of the Royal Hotel[7]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5c1547768ab722e48ecf1942/1629639463137-ORT0XKQ9UBTITZD8GNID/Royal+Hotel.jpg)

![Fig. 3: The purpose-built Library is the building on the far right.[13]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5c1547768ab722e48ecf1942/1629639531617-7LCL4HWN62JI5XBDZDYL/Terrace+Library.jpg)

![Fig 5: The Royal Terrace and Royal Hotel[20]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5c1547768ab722e48ecf1942/1629639673586-Q5A6HA2KV6GTL3XYO034/Royal+Terrace+and+Hotel.jpg)

![Fig. 1: A first edition of Sense and Sensibility in original boards.[1]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5c1547768ab722e48ecf1942/1619535717182-34L1QYQ6LA7EAFN27CT2/Sense-Sensibility-books.jpg)

![Fig.2: Title page of a first edition. [2]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5c1547768ab722e48ecf1942/1619535750164-2U0NRGKHELGXB0R6NVGF/Sense-Sensibility-Title.jpg)

![Fig. 3: Marianne and Elinor [5]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5c1547768ab722e48ecf1942/1619535772229-0OP9AX8OFAOH0QKW9L2K/Sense-Sensibility-illustration.jpg)